The Open Backdoor: Is Your Mine or Infrastructure Hackable?

Pooria Madani, President, AlecTech

Ali Siamaki, Business Development Manager, Tony Gee and Partners

A decade ago, geotechnical monitoring was probably the most secure data stream in the industrial world. The security model was beautifully simple: an air gap. If someone wanted to compromise a vibrating wire piezometer, they'd need to physically drive to the site, hike to the borehole, and plug a cable into a readout box. The attack surface was physical, visible, and easy to control.

Those days are gone.

Today's industry demands real-time insights. We've moved from manual readouts to the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), deploying 4G/LTE gateways, LoRaWAN nodes, and cloud-based visualization platforms. This digital transformation has revolutionized risk management by giving us instantaneous data on structural health. But it's also introduced a new, invisible risk. By connecting critical infrastructure, tailings dams, subway tunnels, bridges, to the internet, we've inadvertently opened our assets to attack.

For Asset Owners and Project Directors, the question is no longer if your instrumentation system is vulnerable. The real question is: Do you know who currently holds the keys to your data?

This article explores the specific vulnerabilities in modern geotechnical telemetry, explains the difference between "Data Confidentiality" and "Data Integrity" attacks, and offers a practical framework for securing the Geotechnical IIoT.

The New Threat Landscape: Why Would Anyone Hack a Piezometer?

When we picture cyberattacks, we usually think of ransomware hackers locking corporate laptops and demanding Bitcoin. In that context, a geotechnical sensor seems like an odd target. Why would anyone care about pore pressure readings?

In critical infrastructure, the threat isn't financial extortion, it's Data Integrity.

The "False Calm" and "False Panic" Scenarios

Operational decisions in mining and construction are driven by data. A Site Superintendent evacuates a pit based on radar readings. A Dam Safety Engineer authorizes a tailings lift based on piezometric levels. If someone can manipulate this data stream, they can trigger catastrophic real-world outcomes without ever touching the physical asset.

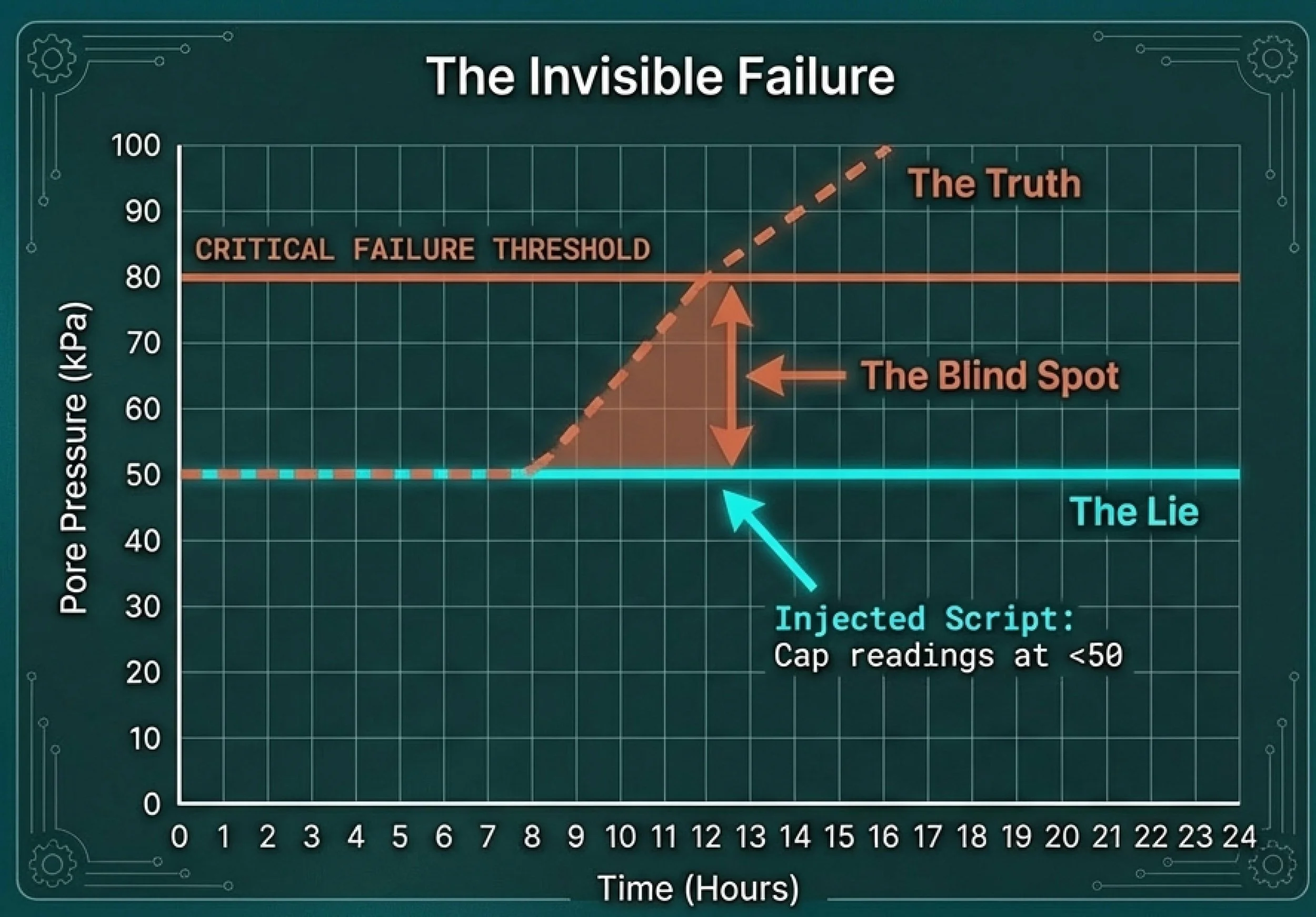

Scenario A: The False Calm (Masking Failure)

Picture a Tailings Storage Facility (TSF) approaching critical stability limits. A hacker gains access to the data aggregator and injects a script that caps all pore pressure readings at a "safe" value of 50 kPa. Meanwhile, the actual pressure climbs to 80 kPa, but the control room dashboard shows a flatline. The alarms never trigger. The dam fails because someone anesthetized the digital nervous system.

Scenario B: The False Panic (Operational Disruption)

Or consider the opposite: a hacker injects a sudden, synthetic spike in slope displacement data. The automated system triggers a Level 3 Emergency Evacuation. The mine shuts down. Production halts for 48 hours while engineers verify stability. This "digital prank" costs millions in lost revenue and reputational damage.

Here's the new reality we need to accept: Data Integrity IS Physical Safety.

The Vulnerability at the Edge: The "Shadow IT" Problem

The weakest link in the geotechnical security chain is rarely the cloud server, whether it's AWS or Azure. It's almost always the "Edge Device", that gateway or logger sitting in a plastic box on a construction site.

This vulnerability gets worse because of something called "Shadow IT." Geotechnical engineers, frustrated by slow corporate IT procurement, often take shortcuts. They buy a generic IoT gateway with a credit card, pop in a consumer SIM card from a convenience store, and deploy it to the field.

That device just became a rogue computer connected to company assets, completely invisible to the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO). It's unmonitored, unpatched, and often completely unsecured.

The "Admin/Admin" Crisis

Here's an open secret in the instrumentation industry: thousands of active cellular gateways are currently running with their default factory credentials.

How it works: Many industrial gateways broadcast their MAC address or model number over local Wi-Fi or Bluetooth for configuration purposes. A malicious actor can drive within range of a construction site, identify the device manufacturer, look up the default manual online, and log in using credentials like "admin/admin" or "1234."

What happens next: Once they're in, the attacker has root access. They can alter calibration factors, disable alarm notifications, or use the gateway as a pivot point to attack the broader corporate network.

Securing the Wireless Last Mile: LoRaWAN and Mesh Risks

The industry has quickly adopted wireless protocols like LoRaWAN (Long Range Wide Area Network) and proprietary mesh networks to connect sensors to gateways. These low-power protocols are great for battery life, but they need specific security configurations that often get overlooked during rushed deployments.

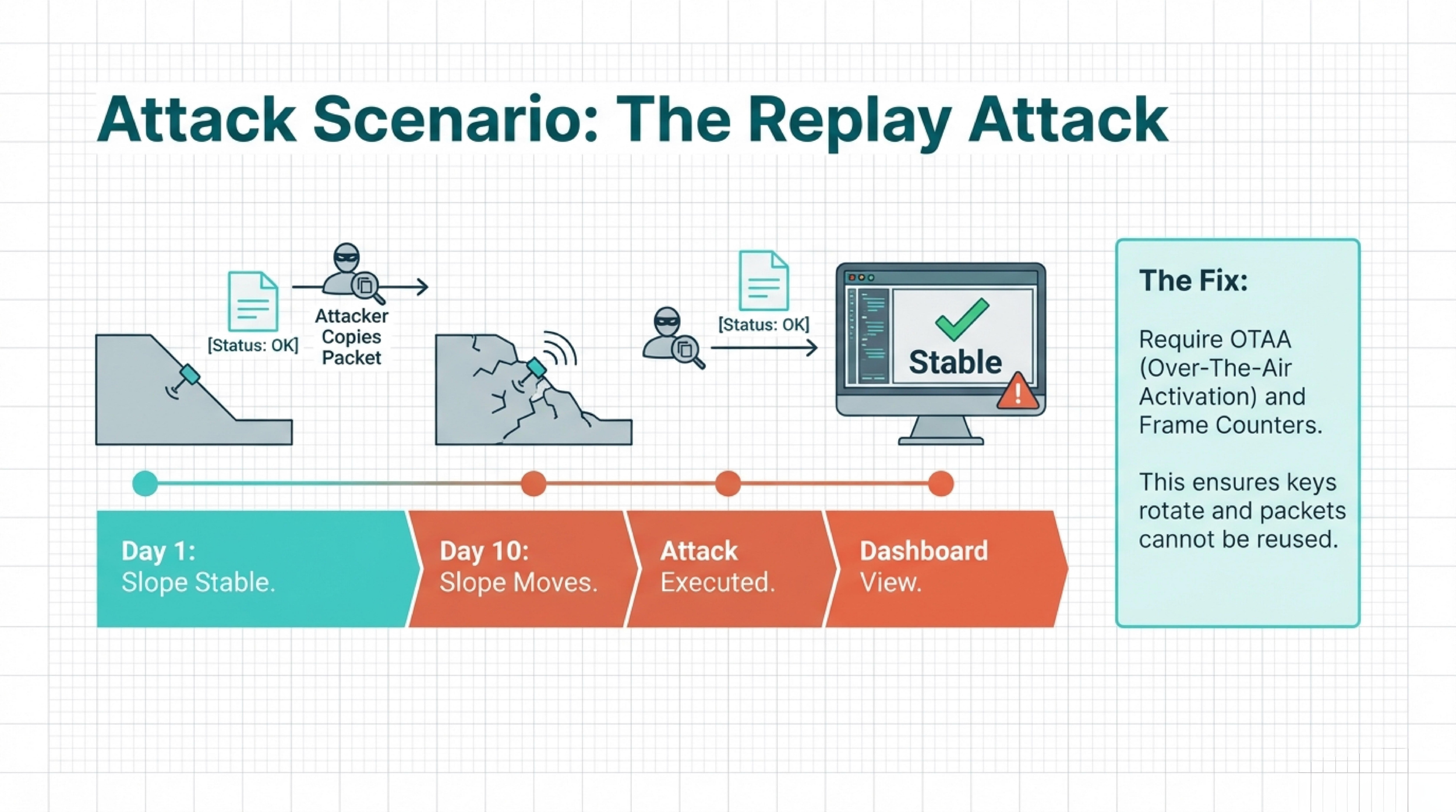

The Replay Attack

Wireless data packets travel through the air. Any radio receiver tuned to the right frequency can "hear" them. While the payload is usually encrypted, the metadata often isn't.

The vulnerability: If a network uses static session keys (common in older deployments), an attacker can capture a valid data packet—say, "The slope is stable"—and record it. Days later, when the slope actually starts to move, they replay that old, stable packet to the gateway. The system accepts it as valid because the key matches.

The defense: Systems need to enforce Frame Counters (verifying that packet #50 comes after packet #49) and use OTAA (Over-The-Air Activation), which generates dynamic, temporary session keys that expire, making captured packets worthless.

The Physical Compromise

Unlike a server locked in a data center, a geotechnical node is bolted to a wall in a public area or on a remote mine bench. Physical theft becomes a cybersecurity risk.

The risk: If someone steals a LoRaWAN node, can they extract the network keys from the chip? In many cheaper devices without secure elements, the answer is yes. With those keys, they can spoof data from any sensor on that network.

The defense: High-security projects should require devices with a Secure Element (SE)—a specialized hardware chip that stores cryptographic keys in a way that prevents extraction, even if the device is physically torn apart.

The Network Layer: Public vs. Private Connectivity

How does data travel from the site to the cloud? This "backhaul" layer is critical.

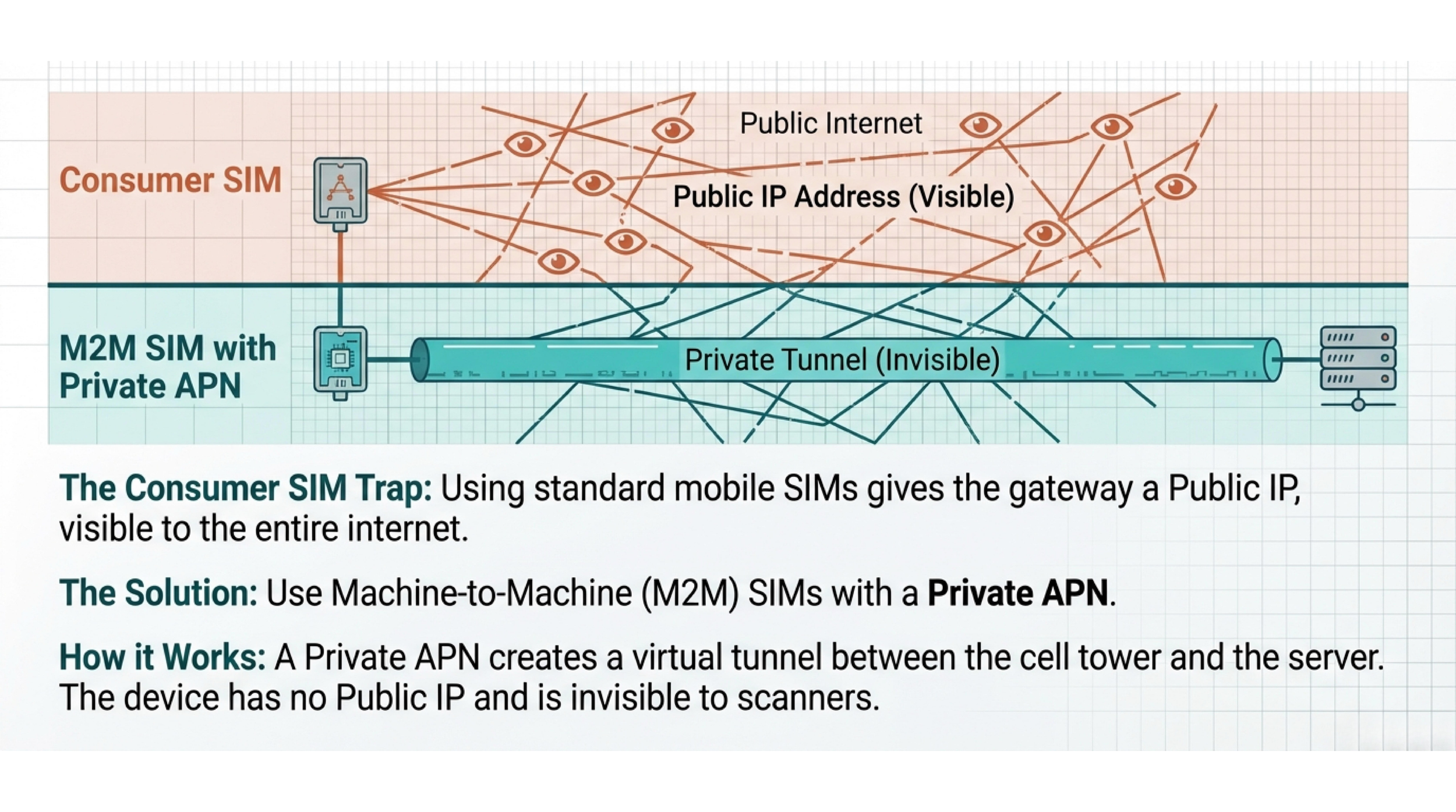

The Consumer SIM Trap

Most ad-hoc monitoring systems use standard consumer SIM cards—the same ones in mobile phones. These cards give the gateway a Public IP Address (or a Carrier-Grade NAT address that's still accessible from the public internet).

The threat: A device with a public IP is visible to the entire world. Automated bots constantly scan the internet for open ports (like Port 22 for SSH or Port 80 for web access). If your gateway is visible, it's getting probed thousands of times a day.

The solution: Critical infrastructure monitoring should strictly use Machine-to-Machine (M2M) SIM cards configured with a Private Access Point Name (APN). A Private APN creates a virtual tunnel between the cell tower and your server. The device never touches the public internet. It has no public IP. It's invisible to scanners. To access it, you need to be inside the corporate VPN.

MQTT and Encryption

For data transmission, the industry standard is MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport). It's lightweight and efficient. But default MQTT often transmits unencrypted text.

The requirement: All data transmission needs to be wrapped in TLS 1.2 or 1.3 (Transport Layer Security). This ensures that even if someone intercepts a data packet at the ISP level, it looks like gibberish. Engineers should verify that their data loggers support MQTTS (Secure MQTT) and that certificate validation is enabled.

A Framework for Cyber-Physical Hygiene

You don't need to be a Certified Ethical Hacker to secure a geotechnical site. Project Managers and Lead Engineers can build a robust security posture with a "Cyber-Physical Hygiene" checklist.

Phase 1: Procurement & Setup

Mandate "Security by Design": When writing the RFP for instrumentation, include a cybersecurity clause. Require vendors to prove their devices support encrypted storage and secure boot.

The "No Default" Policy: Before any device leaves the office, change its default password. Use a unique, strong password for every gateway. Store these in a secure, encrypted password manager (like Bitwarden or KeePass)—never in a spreadsheet on a shared drive.

Segregate the Network: Don't put IoT gateways on the same network as corporate business operations (HR, Finance). Place them on a dedicated IoT VLAN (Virtual Local Area Network) with no access to other internal resources.

Phase 2: Deployment & Operations

Disable Unused Ports: If the gateway has USB ports, Bluetooth, or Wi-Fi that aren't needed for daily operation, disable them in the firmware. Simple rule: if you don't use it, turn it off.

Firmware Patch Management: IoT devices are software. They have bugs. Vendors release patches to fix security holes. Set up a quarterly maintenance window to remotely update the firmware on all field devices. A device running three-year-old firmware is essentially a sitting duck.

Phase 3: Access Control

The "Read-Only" Standard: Who actually needs to change alarm thresholds? Probably just the Lead Engineer. Everyone else—clients, project managers, regulators—should have viewer access only. Implement strict Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) on the cloud dashboard.

Revocation Protocol: When an employee leaves or a contractor finishes their scope, revoke their access to the data platform immediately. "Orphaned accounts" are a primary entry point for malicious insider attacks.

Conclusion

For decades, Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) existed in separate worlds. The IT team managed email servers; the OT team managed vibrating wire sensors.

Those worlds have collided. Today's Geotechnical Engineer sits right at the intersection. We can't afford to be "just" rock mechanics experts anymore. We need to become stewards of data integrity.

Securing the Geotechnical IIoT doesn't require a massive budget or a dedicated security team. It requires awareness. It requires the discipline to change a password, the foresight to use a private network, and the understanding that in a connected world, a secure sensor matters just as much as a calibrated one.

The ground is moving. The data is flowing. It's our responsibility to make sure the story the data tells is the truth.